Dr Paul Bevan is a Research Associate and Teaching Fellow at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) where he teaches courses in the History and Culture of China and Classical Chinese. He has taught Modern Chinese Literary Texts at the University of Cambridge and at the University of Oxford where he recently completed a 14-month period as Departmental Lecturer in Modern Chinese Literature and Lecturer in Chinese at Wadham College.

Paul obtained his PhD from SOAS in 2012 with a dissertation entitled Manhua Artists in Shanghai 1926-1938: From Art for art’s sake to Wartime Propaganda. His wide-ranging research interests include the impact of Western art and literature on China during the Republican period and the study of inscriptions on eighteenth-century art objects. In the latter capacity he has translated all inscriptions on Chinese art objects in the collection of Her Majesty the Queen soon to be published as part of a three-volume catalogue. He has also acted as Historical Consultant for the Royal Geographical Society and as Ethnographic Consultant for the Royal Albert Memorial Museum, Exeter. He recently completed a year as Edison Visiting Fellow at the British Library where he worked on a project entitled “Classical Music in the Jazz Age.”

Paul’s forthcoming book A Modern Miscellany: Shanghai Cartoon Artists, Shao Xunmei’s Circle and the Travels of Jack Chen, 1926-1938 is soon to be published by Brill, Leiden. In this book Paul explores how the cartoon (manhua) emerged from its place in the Chinese modern art world to become a propaganda tool in the hands of left-wing artists. The artists involved in what was largely a transcultural phenomenon were an eclectic group working in the areas of fashion and commercial art and design. The book demonstrates that during the build up to all-out war with Japan the cartoon was not only important in the sphere of Shanghai popular culture in the eyes of the publishers and readers of pictorial magazines but that it occupied a central place in the primary discourse of Chinese modern art history.

Paul has also worked extensively as a musician and his engagement with eighteenth-century European music, both as a researcher and performer, informs his studies on the history of art during this period.

The project so far

As British Inter-University China China Post-doctoral Fellow and Consultant I am working with the National Trust and the University of Manchester on a project concerning two eighteenth-century clocks in the collection of Anglesey Abbey in Cambridgeshire.

The history of these impressive objects, which I’m now in the process of unravelling, is both fascinating and complex. One of these clocks, known at Anglesey Abbey as the “Pagoda Clock”, has recently been carefully and painstakingly conserved by the clocks department at West Dean.

During the conservation process several small scraps of paper thought to be from a Chinese newspaper were found in the clock. They had been used as padding to pack the enamel panels found on the clock, possibly to secure them in transit. The discovery of these scraps of paper was taken as proof that the clock had spent some time in China.

From what I’ve been able to discover in the first stages of the project, it can be shown that another clock, described in the National Trust collection as the “Tower Clock”, also spent some time in China. Whilst examining the clocks with Christopher Calnan of the National Trust, we found, scratched crudely inside the clock, two Chinese characters, no doubt inscribed to identify the panels when the clock was being assembled. One of these characters very clearly reads you 右(right) and the other, which is much less clear, appears to read shang 上(upper); together they translate as “upper right”. The histories of both the Tower Clock and the Pagoda Clock form the basis of the research project.

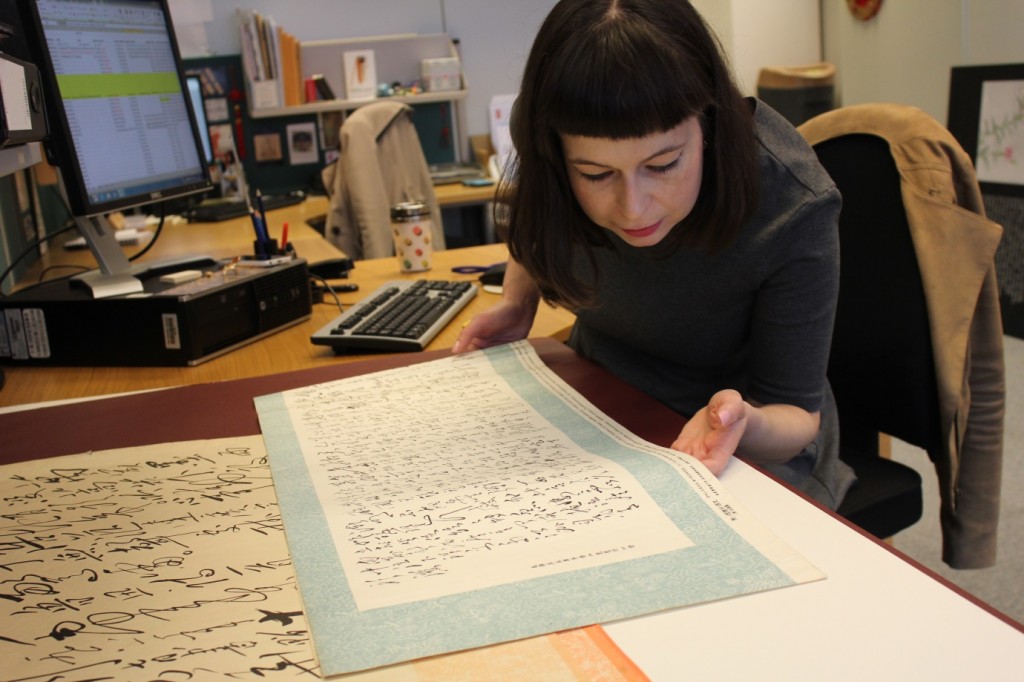

By deciphering the text on the scraps of paper found in the Pagoda Clock, it has been possible to estimate the time when the clocks were last in China. Three different types of paper were found in the clock. These pieces are really nothing more than scraps and there is a strong possibility that the three types of paper were used by clock repairers at different times. The pieces of paper are

Letter Paper- These two small scraps of off-white paper do not tell us anything significant about the history of the clock as there are only two characters, written in ink, found on one of the pieces and a minute fragment of another single character on the other. The readable characters are si jiao 四角 (‘four corner’ or ‘corner four’) and may have been written on the paper simply to indicate that this was to be used to repair ‘corner four’ of the clock.

Scraps from a Single Sheet- No complete sentence can be found here, but it has been possible to identify the origin of the woodblock printed sheet by the vocabulary used. There are two possibilities: either it is part of a leaflet giving the instructions for a type of lottery popular at the end of the nineteenth century, or it is part of a lottery ticket itself. The lottery, known as Weixing 闈姓, required the player to guess the family names of the candidates put forward for the imperial examinations and the order in which they would be placed in the exam. This type of lottery was particularly popular in Southern China in the 1880s and 1890s. It came to an end when the Chinese civil service examination system was disbanded in 1905. These scraps of paper do not tell us all that much about the clock except that it was in China during the late nineteenth century.

Newspaper- The scraps of newspaper are clearly of a later date as can be seen from the type of print used and the vocabulary found within the text. However, these also present problems, as again, no complete sentence is decipherable. The actual date of the newspaper is not shown on any of the fragments, so dating the scraps has had to be done with reference solely to the vocabulary.

The earliest year in which the newspaper could have been published is 1912; the year of the founding of the Chinese Republic. This can be seen from the official title Guowuyuan 國務員 and related terms, found within the various fragmentary sentences. The latest possible date can also be deduced from the vocabulary and this is October 1914; the year that Shuntianfu 順天府 (Shuntian Prefecture), as mentioned in the text, was abolished as an administrative unit.[1] After this time it became the Jingzhao difang 京兆地方 (Capital district); part of the city of Beijing.[2] Of course this method of dating is by no means fool proof as the text could be referring to events which had occurred before the time of publication but I would suggest it is likely to be more or less accurate and, after all, at this stage it is all we have to go on.

This has been the first step in a long process in discovering the history of the clocks at Anglesey Abbey and when they were last in China. More on this and on how I have been able refine these dates further will appear in my next post.

1] Zhongguo lishi diming cidian 中國歷史地名辭典 (Dictionary of Chinese Historical Place Names). Nanchang: Jiangxi jiaoyu chubanshe, 1986, p. 651.

[2] Dong, Madeline Yue: Republican Beijing: The City and Its Histories. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003.